https://www.cas.cn/cm/202410/t20241021_5036686.shtml

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-024-01984-8

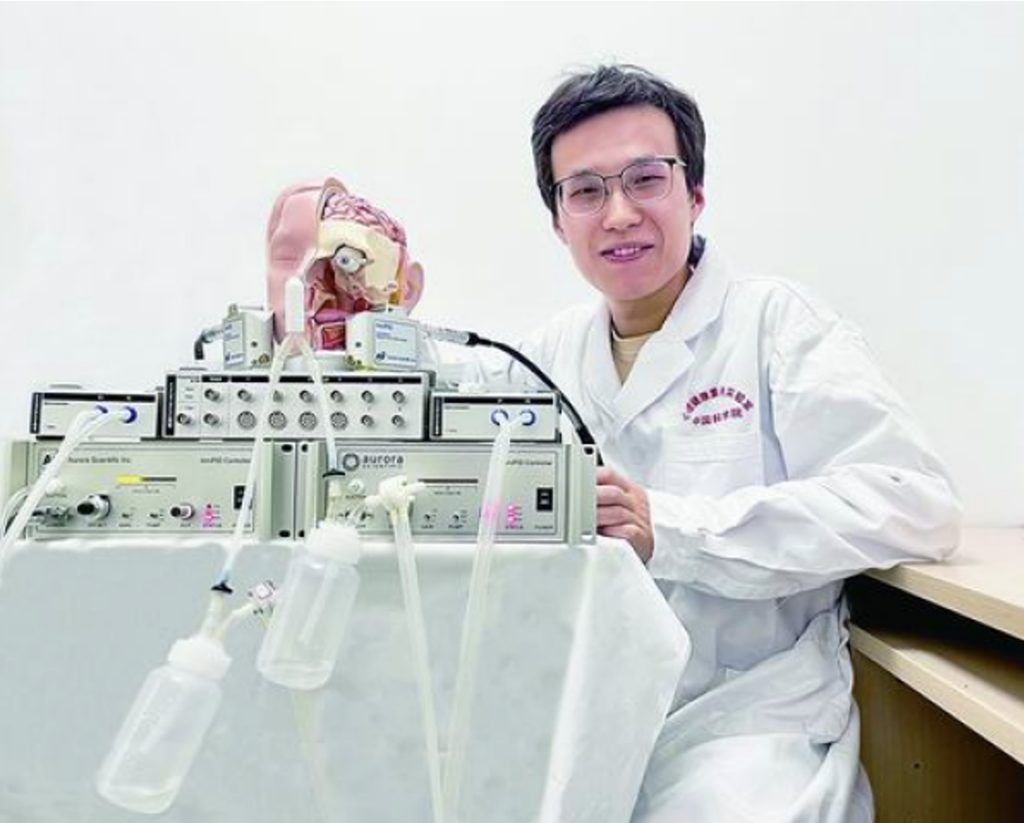

CAS Institute of Psychology measured the temporal accuracy of the olfactometer with the help of a high-speed ion detector and an airflow meter.

Car exhaust, the aroma of coffee, the smoky smell of barbecue… Walking on the street, people can judge the changes in their spatial position through different smells, and unconsciously produce pleasant or unpleasant emotional reactions. Nevertheless, compared with vision and hearing, smell is often considered to be the slowest sense of human response. Part of the reason is that smells are erratic and people usually can only perceive smells when they inhale, which makes it difficult to capture the temporal resolution of human smell with high precision in experiments, thus limiting people’s accurate assessment of the speed of smelling and the ability to distinguish tastes.

With a high-precision “olfactometer”, the understanding of the temporal resolution of human olfaction was raised to the “millisecond level”, and found that the human sense of smell can perceive the difference in the order of two odor molecules presented at an interval of 60 milliseconds – 1/3 of the duration of a blink.

The instrument uses the negative pressure generated by inhalation to control the airflow, and then transmits the smell to the nasal cavity. At the same time, we use a one-way valve to control the opening and closing of the smell channel. The opening of the one-way valve is due to the pressure difference generated by inhalation. When not inhaling, the valve remains closed to prevent the smell from diffusing in the form of Brownian motion.

The research team presented different sequences of odor molecules to the subjects – including compounds similar to apple, onion, lemon, and floral odors, and controlled the relative time interval of these odor molecules to vary in the range of about 20 milliseconds to 400 milliseconds to measure the subjects’ olfactory time sensitivity. In addition, they asked the subjects to rate the similarity of the components of the odor mixture and the individual odor. The study found that when the interval between the presentation of the two odor molecules was only 60 milliseconds, the subjects could distinguish the similarities and differences of the odor sequence composed of the two. “60 milliseconds is about 1/3 of the length of a blink, which is close to the visual resolution of red and green flashes.” Zhou Wen said that in the context of the two odor molecules presented in sequence and reverse order, the absolute time difference is equivalent to two 60 milliseconds, that is, 120 milliseconds. The study also found that when the presentation interval of the two odor components was extended to 100-200 milliseconds, the subjects felt that the mixture smelled more like the odor component presented first. This shows that in the perception of odor mixtures, the odor component presented first is more important for the perception of the overall odor.

The importance of smell should not be underestimated for both humans and animals. Smell plays a vital role in emotional regulation, social interaction, and even disease prediction in humans and animals. Take bees as an example. Their sense of smell is not only used to find food and navigate, but also plays an important role in social communication. Perception research is an important research topic in basic psychology, a secondary branch of psychology. In the past 15 years, a series of studies led by Zhou Wen and her team have shown that human sense of smell is much more acute than imagined. For example, smell can not only serve as an important clue for spatial navigation, but also affect people’s perception of visual objects, and even perceive gender and sexual orientation based on different smells.

In the authors’ view, there is still much room for research on olfaction. For example, although the research on visual and auditory coding has been relatively in-depth, the research on “smell coding” is still a shortcoming. At the same time, modern robots already have vision and touch, but have not yet fully developed olfactory functions. In the future, if olfaction is incorporated into the robot’s perception system, it may help open up new application areas.